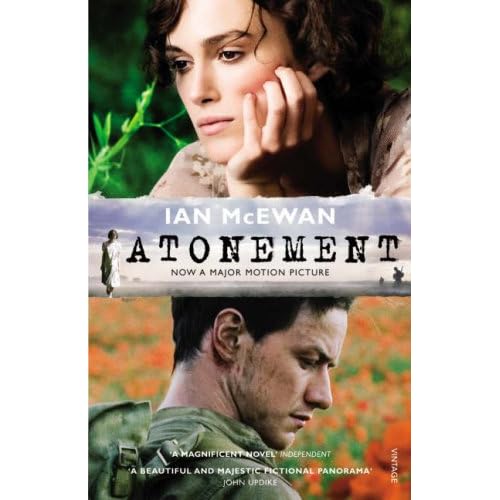

Ian McEwan's Atonement, released in 2002 (just goes to show how long it takes for a book to be turned into a film when it's optioned) was recently released in the cinemas (and is soon to be removed - so get down there quick).

Ian McEwan's Atonement, released in 2002 (just goes to show how long it takes for a book to be turned into a film when it's optioned) was recently released in the cinemas (and is soon to be removed - so get down there quick).As imdb's plot summary states:

A British romance that spans several decades. Fledgling writer Briony Tallis, as a 13-year-old, irrevocably changes the course of several lives when she accuses her older sister's lover of a crime he did not commit.Funny that that is a succinct description that avoids entirely the crux of the story. Imdb has a second summary that better catches the hook:

The important thing is in the way Briony misconstrues the events she part witnesses on one Summer's day in 1935.

In the summer of 1935, 13-year-old Briony Tallis observes a flirtation between a servant's son, Robbie, and her older sister, Cecilia, that she childishly misconstrues. Briony's misunderstanding leads to a terrible crime whose consequences follow them through World War II.

Which, without giving away any of the significant plot points, brings me to the interesting manner in which these moments of misconstrue-ination occur. We open with Briony, she is a 13 year old writer with a big old imagination and a crush on Robbie. He in turn loves Cecilia and on three separate occasions Briony mistakenly walks in at the wrong moment of the development scenes in Robbie and Cecilia's relationship. And each time she adds a bit more of her own ideas about what is really going on.

I'm not sure how this comes across in the book (will have to go hunting - watch this space), but in the film each moment is developed first from Briony's point of view, running with her through a scene until she stumbles upon the end of a situation between Robbie and Cecilia, or regarding the two. And sure enough they seem quite odd/erotic/troubling.

We, the viewer, are then drawn back in time to witness the story from Robbie and Cecilia's point of view, showing us the real and, at first, innocent incidents.

At the end of every scene we are again put back into Briony's position - this is important! Though we begin to get momentary repeats of information, and having witnessed the end to these scenes already with Briony, when they are shown in full from Robbie and Cecilia's point of view, they lose their suspense (we know the outcome and that Briony will witness it).

However, the film makers and, I'm sure, McEwan have taken the decision to make Briony the protagonist (if not the main character - I'm still not sure if she's both, or if Robbie is in fact the protagonist... hmmm), and as such we need to be put back into Briony's frame of reference.

Why? Because we need to understand why she suspects Robbie of... the final deed... despite what she really sees, and what we, the viewer, really know. And why she chooses to lie to the police. Without the constant start and return to Briony's point of view the viewer would lose any and all empathy/sympathy with Briony's character and she might come off as vengeful and childish than she does.

For me the sour note in all this is that it removes possible moments of future surprise - like Columbo we know who the real culprit is from the off (and don't be fooled into thinking that in a Dickensian way all badguys will pay for their crimes, this isn't that kind of story). But I can understand it is mere fallout from the purpose of the plot - the atonement itself.

It makes for a great film, though the drawn out scenes when the main characters are torn apart do begin to drag, but then you come to appreciate this at the end, with the final reveal regarding what you've been watching - interesting also, and partly reminded me of The French Lieutenant's Woman (but not implicitly).

No comments:

Post a Comment