I Am Legend is in its fourth incarnation, following the book, by Richard Matheson, the Vincent Price film The Last Man, and Charlton Heston's The Omega Man. A story that is half character-play on the loneliness and psychological effects of being without human contact for three years and half horror-actioner, which, for the most part, works on both counts.

I Am Legend is in its fourth incarnation, following the book, by Richard Matheson, the Vincent Price film The Last Man, and Charlton Heston's The Omega Man. A story that is half character-play on the loneliness and psychological effects of being without human contact for three years and half horror-actioner, which, for the most part, works on both counts.I'm not going to discuss the film as a review, because you can get those all over the place on the net. You don't need me for that. What interests me is the adaptation aspect of going from a book to a film. I gave a brief rundown of the book back in June, and you can read that here - again it's not a review as such, and I was also strict with myself not to give the ending away - just in case the new film ended on the same note.

Sadly it does not, and I will have to break the Spoiler code in order to discuss it - but I will advise you when I'm about to do that. So, what am I trying to do here? I'm trying to highlight areas of failure between adaptations.

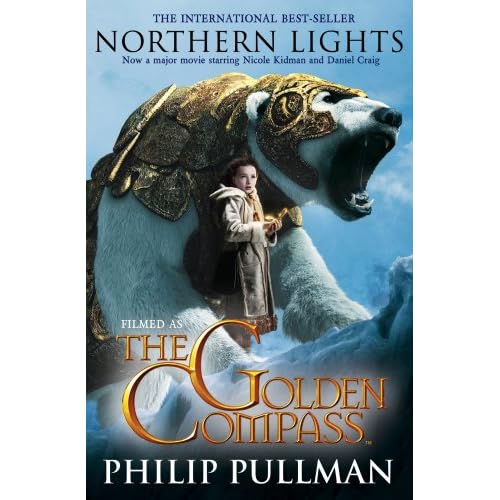

Let me first say that I am usually of an open mind with book to film adaptations - Lord of the Rings I accepted with no concern about the little changes, the minutiae omitions and the jiggling of the timeline between The Two Towers and Return of the King. Harry Potter too would have been far too long with everything left in. LA Confidential excelled in taking a different course, Equilibrium's failings were elsewhere (and following the book would have made for a weak film anyway), The Golden Compass had lost nothing in its screen translation... so, why is it that, despite having already intended to write about the adaptation of I Am Legend, I'm disappointed by the options the filmmakers chose?

General Troublespots

I can accept much of what the film is because it is essentially about the isolation, and while this makes for slow moments that probably won't lend themselves well to repeat viewing it does draw you in to Robert Neville's inner world. However, in typical Hollywood fashion, explanations are glossed over with shortcuts or ignored. For example, in the book Nevilleis immune because, he suspects, he was bitten by a bat when holidaying in Panama. The film gives no explanation of why Neville (of all people) is immune, and just so happens to be a Colonel and the Scientist attempting to stop the virus.

Secondly, Neville falls into a trap that throws the last half of the film into its tense-filled action sequences (which I'm all for). The nature of the trap however is questionable. The trap is designed exactly the way Neville has been setting his traps (he captures the dead/vampires/mutants / infected so as to test his serum on them) and is far too elaborate for the infected to concoct, yet Neville (having lost his marbles for little apparent reason, and no, I didn't buy it) gets himself caught in the trap and wakes as the sun goes down with the Alpha Male infected and infected dogs bearing down on him - it seemed to present the infected as having prepared everything, and yet this couldn't be true (since the only other things they do is attack, climb, destroy, headbut and eat). The flipside is that we hadn't had enough evidence of Neville's mini-psychosis. He just wouldn't have put himself in that position and we needed more examples of him losing his marbles (more than just wanting to chat to the lady in the shop).

There is a big argument in favour of the infected having set the trap - the Alpha Male appears to have a beef with Neville (1. When Neville takes the female infected, the Alpha Male risks the UV light. 2. The Alpha Male is at the trap, clearly intent upon getting Neville - he at least has higher brain functions. 3. In the denouement he pushes past all the others and is the one to headbut the partition, trying to get at Neville). In the book Neville's old neighbour seems to portray the more self-aware infected and this is potentially a throwback to that, though in the case of the film it is poorly pulled off, since those discussing this point cannot agree on a solution. There is insufficient evidence for either camp to be right, and this is the fault of the filmmakers.

Psychological Evacuations

A big part of the book is the psychology of the vampires, that the virus as a biological agent that alters the victims physically and psychologically. There is no reason for them to fear mirrors or crosses and yet they do. They are allergic to a compound in garlic and their skin is too fragile to withstand UV light. All fair enough. Neville is very interested in trying to understand why they fear mirrors and crosses, since neither can harm them in anyway - a throwback to an indoctrinated belief by the infected that they really are vampires.

This is a wasted opportunity in the film where it prefers to deal instead with the God debate (which is actually shoe-horned in at the last minute). The book is about psychology to its very core: Neville dealing day-to-day with his isolation and the loss of civilisation; the two kinds of infected and their psychological fears; and, the book's outcome which is a brilliant twist on the notion of being a legend - more on this later.

Unfortunately the film eschews the investigations of psychology by labeling the infected thusly (instead of vampires). As such it places the badguys in the typical Hollywood positions of the brainless goons whose only purpose is for in-scene tensions and action sequences (the Alpha Male aside).

The Ending (Spoilers)

So, here we are. I can cope with much of what went on with the film. I don't mind that Neville was a colonel and not a normal guy, that his family died in a helicopter crash and not infected, that its present day, not the 50s, that his day to day business and what he endures at night is completely different, he has a dog from the start, even that he isn't infiltrated by another woman (of questionable origins). It's fine - films and novels work differently and have to rely on their own toolkits to keep audience interest.

What didn't work was...

1. God versus Science

I suppose I have to give the film credit for trying to argue this case. The book is clearly pro-science as the cause and solution. Neville in the film argues for science but when Anna arrives they argue over there being a higher purpose. Given that this is shoe-horned in only once Anna is introduced in the last third we are given a very different story idea from that with which we started.

2. Symbolism

Once we reach the end we have an overt bout of symbolism shoved down our throats. Sam, the dog, watches a butterfly, Marley, Neville's child, makes a butterfly with her hands and Anna has a butterfly tattoo, and upon seeing the tattoo (having previously disregarded Anna's assertion that God has a purpose) remembers what Marley had said and realises God is telling him to act - sheesh! Symbolism in films is meant to be subtle so that those of us who want greater depth to our stories can look for them and discuss what they mean. They're not meant to be used in a way that says: "Look audience, the clues were here all along, this is a story about God's path... yippee!"

It's as cheap as the ending of The Reckoning (don't even get me started). And of course, the first thing we hear when Anna reaches her final destination, is a church bell - oh, wondrous saviour - this seems to be an attempt to appease the Catholic League as a complete reversal to The Golden Compass, by actually saying we must all believe in God.

What we have, as many people have noticed, is 28 Days Later by way of M. Night Shyamalan's Signs. An interesting but wholly flawed concept.

3. Altered States

This, we realise, is meant to draw us away from the original ending (of the book, and possibly of the movie). As a side note there was some hoo-har about the original ending of the film, in that test audiences didn't like it and/or Will Smith gave away the ending during a press conference in Tokyo.

There has been a definite change, since the following image from the trailer, is not in the final film (hmmm)...

4. The Title's Meaning

4. The Title's MeaningI didn't give away the ending did I? Well here we go... In the film Neville gives Anna a vial with the cure and sacrifices himself. She can then travel north (as she was originally going to do), taking the cure with her - the cure being Neville's Legend. Though, really this is just his legacy.

In order to understand just how disappointing this is for those of us who read the book and buy into the original intent of the story, you too need to know the original ending.

5. I Am Legend

In the book there are two types of infected - 1) the dead who are pretty much as they are in the film, mostly psychotic monsters, 2) the living who have the same symptoms (aversion to sunlight and garlic but who still have their own mental faculties).

The fact that there are two kinds is key. In the book Neville goes from building to building locating infected and killing them. They are induced into deep sleeps during the day as a way of keeping away from the light and to Neville, not knowing that there are two kinds of infected, both types look the same. Of course, towards the end we discover that he has been killing both kinds.

The living infected are trying to start a new civilisation. They have become mutated or evolved (if you will) and must put up with what they've got. And they would be able to move on (they too kill the dead infected), but for the fact that the monster, Neville, is killing them. They are in fear for their lives because Neville will come for them and wipe them out.

As such, they set about trying to trap him in order to kill him, and this is why he is Legend. And since the book is all about perceived psychological scenarios and beliefs (isolation / doing good / fear of benign objects such as crosses) and the fact that Neville's actions have made him (as the minority) the monster (the Grendel character). He is a Legend among the living infected.

6. Concept of the Adaptations

Of the other two adaptations, neither chose to use the title I Am Legend, despite Vincent Price's The Last Man Alive being far closer to the original concept. This is ever more interesting when considering that the latest film cops out on the ending, chooses a different theme and subverts the meaning of the title with a weak and saccharine view that seems to work for everyone but those who read the book. I guess they fell in love with the title! But how wrong can an audience's expectations get? With the original two movie adaptations the omition of the original title gives them license to go where they please with the story... with the latest, they're giving a nod to the original text (as they do with much of the concept, character, and idea) but they're relying upon the "coolness" of the title without being gutsy enough to remain faithful to the concept.

Again, the quick and easy answer is that it doesn't matter. It's a title and writers / directors have free license to make a film any which way they please. So, why do I feel it needs to be said to all writers to be true to your audience? Because, as I argued in the latest Litopia Podcast (Is Story Dead?) that an audience does not need to know what will happen at the end before they get there (as Alex Kavallierou stated) but that they need to have a sense of the ending - comedy / tragedy. There are conventions that must be followed.

Akiva Goldsman (prolific Hollywood writer - A Beautiful Mind; I, Robot; The Client) - actually his scripts are standard fare (top-Hollywood grosers certainly, but nothing special) - has been quoted as acknowledging that fans of the book will be annoyed by what happens in the film.

"Fundamentally I think that there's an obligation to attempt to be true in spirit to the source. And you have to make a determination about what the source is…"

Interestingly, another writer made this comment:

Do you know how weird it is to see Will Smith on the cover of a book called "I Am Legend" as the hero of the story only to open up the book and read that the guy is an alcoholic smoker of English-German descent with blond hair, a scraggly beard and blue eyes? It throws you for a second and makes it hard to read at first because you have to push everything you have seen in Warner Bros.' attempts to market this film out of your mind.It is an interesting concept about misleading an audience, and it harks back to the remake of The Italian Job, which wasn't a remake at all - it used names, locations and the mini chase, but replaced absolutely everything else. It comes down to a marketing ploy - the filmmakers aren't making the original because they think they're going their own - better - way, but they are piggybacking off the success of the originals by way of saying to all the fans: "You loved that, you'll love this, and we'll lie by implication because we won't admit until after you've seen it that it's going to end differently."

And while I must say that the latest film version of I Am Legend is good in its own right, we're all missing out on the potential for a much better version (the book version) because the writers think (and have failed) they can do better.

Sigh! Lesson to be learned: follow the original or use a different name.